Upper Missouri River from the Sky

In June 2019, we were fortunate enough to be invited by the infamous Glenn Monahan on a flight tracing the Upper Missouri River from Helena to Fred Robinson Bridge. This flight was not Brett’s first time, which seems understandable considering he worked for the company for 13 years before becoming an owner.

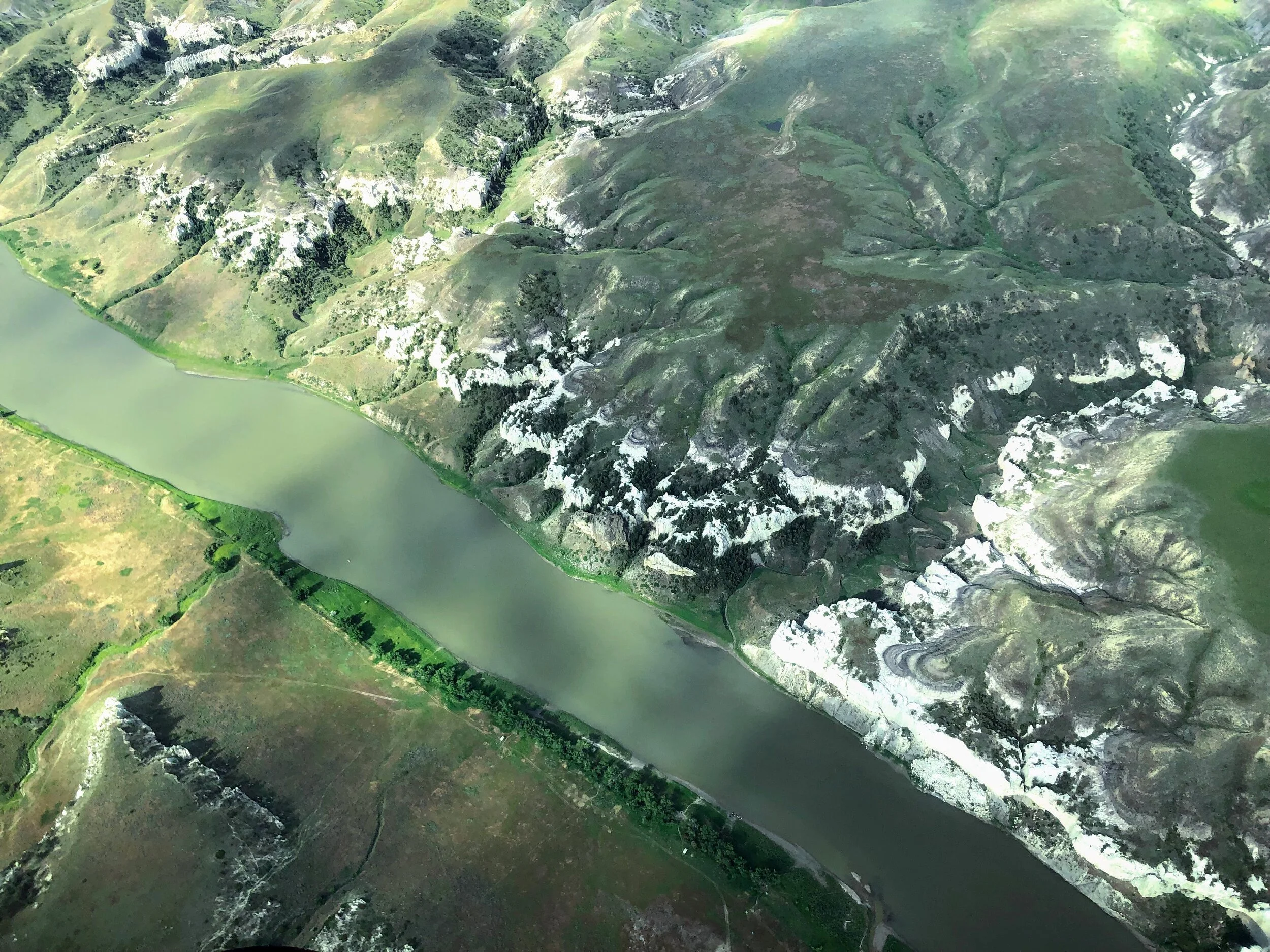

These photos are a journey from the sky of our favorite places on the river. They truly make evident the vast expanse beyond the shores of the river, and, moreover, the deep, twisting, braided gullies, coulees and drainages that form the lower section of the Upper Missouri River Breaks. The “Breaks” referring to the land appearing broken over time by the forces of these features. The images of this landscape evoke power, magnitude and majesty. Who would have thought a river flowing through the prairie would command this presence.

Just wait until you see it from the river!

Note: upon take off, I realized my fancy DSLR camera was present but without a memory card. Darn. These photos were all taken by my iPhone. Pretty good considering.

TIME FOR TAKE OFF!

We look off from the Helena International Airport heading mostly due North towards the Missouri River. We first encountered the Mighty Mo as she transformed from a slow, powerful river into a long, deep reservoir created by Hauser and Holter dams. (In the area of Helena, there are three dams total: Canyon Ferry, Hauser, then Holter). The Holter Reservoir is contained within an area called The Gates of the Mountains and is a famous fly fishing haven better known as ‘The Land of the Giants.’ On a hot summer day, in a drift boat, raft, tube or atop a paddleboard, you can easily see massive trout darting between the tall algae that flourishes in this shallow, warm fishery. If you have a hankering to fly fish, this is your destination.

Past these reservoirs, we flew over the small fishing town of Cascade then towards Great Falls. As you can see, our pilot’s attention was equally split between flying safely and monitoring the looming thunderstorm just beyond Great Falls. This isolated storm would probably not cause a second thought if safely on the ground, but in a small plane, well, it’s like a standing just on other side of a fence that cages a hungry tiger!

My iPhone zooming capabilities were limited, but in the third photo, you can see two of the five dams obstructing the mighty Missouri River yet generating power in the Great Falls area. We often fantasize about how different the town of Great Falls would be if there were not dams…. Not only would you have access to visit the once magnificent and famed Great Falls, but these unobstructed features would also offer whitewater boating opportunities, fertile fishing grounds and, of course, a significantly long stretch of river. Oh to dream.

(Click on any picture to enlarge.)

White Cliffs of the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, River mile 42-88

We b-lined it for the White Cliffs, cutting off just a few miles to beat the looming weather. Right away and rather ironically, I noticed the White Cliffs weren’t as grandeur from the sky as when you float past in a canoe. Those towering geologic wonders that “exhibit a most romantic appearance.... the soft sand clifts woarn into a thousand grotesque figures… made to represent the eligant ranges of lofty freestone buildings... “ wrote Meriwether Lewis on May 31, 1805, honestly, did not command the same response from above. More impressive were the twisting, braided coulees beyond the river banks, many of which I have never explored, and the majority of these hidden outlets are not detectable from a canoe. I noted several drainages exposing white sandstone, specifically around Arrow Creek, river mile 76.5 right hand side, that I intend to explore one day.

The first major landmark that got us excited was Eagle Creek, river mile 56 and Lewis and Clark Expedition campsite May 31, 1805. This is the first stop for most canoe trips through this section of the Monument. In the first picture, the long grove of trees on the left side of the bank is Eagle Creek Campground. Just to the left of the trees, you can see the Eagle Creek drainage, a road that allows the BLM to access the toilets, and to the right of the grove of trees and straight back, is Neat Coulee. Venturing back into Neat Coulee is one of our favorite hikes - you can complete a loop that includes a bit of rock scrambling, walking through a slot canyon that narrows to about 5 feet across, gain a vantage point on top which feels like ‘walking on the moon' and more. The second picture is almost directly above the camp. Notice here that although the prairie is vast and civilization is far away, there are patches of farmed land very close to the river corridor. Although communities are far, evidence of human life is close.

Following the river, we came upon another famous landmark, Citadel Rock river mile 62, named by steamboat captains as a way to establish their location on this enormous river as they labored upriver fully-loaded with passengers and goods to be, hopefully, delivered all the way to Fort Benton. In the first picture, the number “1” designates this famous and towering igneous intrusion. Passing by this figure in a canoe, one generally stops paddling and offers reverence. Doesn’t look that grand now does it!

The number “2” indicates Hole in the Wall Campground, river mile 63. Below the number “3” is the white sandstone cliff formation straddled and reinforced by igneous dikes that, at the very end, offers the infamous Hole in the Wall, river mile 63.8, which is an actual hole carved out by the wind. This is another important and loved hike with an incredible vantage point. The second picture shows just how incredibly mighty the river is compared to our tiny canoes. The hike is not very far, perhaps a mile and half one way, but it only takes a little elevation gain to truly be on top of it all. The third picture is looking directly at the Hole in the Wall feature. Notice the lone tree at the bottom third on the far right of the picture. This is where we park our canoes to go on the hike to the hole.

After a few more riverbends, we came upon the feature across from the camp, Slaughter River, river mile 76.5 and Lewis and Clark Expedition campsites May 29, 1805 and July 7, 1806.

Although the picture quality leaves something to be desired, it does offer a ‘bird’s eye view’ of just how expansive this particular feature is. The camp is located towards the left hand side of this feature and across the river in the grove of trees. Every time I spot this feature from upriver, I am always amazed at just how long it takes to get around the corner, to the end and to camp. This is certainly one of my favorite locations for sunrises. The color of the water and glowing morning sun on this feature is unrivaled.

Just past this feature on its left hand side, is the drainage Arrow Creek. One of my favorite stories of Native Peoples is the magical legend of Arrow Creek recorded by James Schultz and told by his wife. You can find this story and many more in the official guidebook and history digest available through our website. This is also the one of the most intriguing drainages I spotted from the sky that entices exploration.

There are several dispersed campsites past this developed boat camp, however, Slaughter River, with its vault toilets, log cabin shelter and picturesque view makes it a favorite last campsite for many boaters through the White Cliffs section.

Judith Landing and the Judith River: an exit point for many, a halfway and restock point for some. The Judith River is small but stunning. The valley is home to a large portion of the American Prairie Reserve - an organization attempting to return the prairie to its former glory through land acquisition. One day we might see Bison on the river again. At Judith Landing, one sees evidence that civilization still exists but remains far away. Here, intrepid river goers can restock if they planned ahead or have nice friends on water, food and other essentials, like cold beer and portable toilet components. After the hustle of restocking and reconfiguring the gear in the canoes, the ‘shove off’ this bank is one of my favorite feelings during any trip.

Badlands or “Breaks” of the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, River mile 88-149

The Badlands or better known as the “Breaks'“ is equally stunning and vastly different from the White Cliffs. This remote section of the Upper Missouri River gets its name because, from above :-), the drainages funneling from the prairie uplands to the river corridor below appear to be ‘breaking’ the land. Most guides acknowledge the White Cliffs are amazing and can’t help but be pleasing, but most will also report that the Badlands are their favorite. Many factors contribute to this preference: there are generally less people, more wildlife and you generally get a feeling that you are deeper in the wild. (There is also something that occurs after a few days on the river. We call it ‘when the magic happens,’ and almost overnight, you can feel the group settle into river life, anxieties fade, friendship develop and the group generally starts functioning like a well-oiled machine. The grandeur and famous quality of the White Cliffs offers a satisfactory distraction from the beginning trip jitters. The Badlands get happy campers ready to settle in for the long haul.)

Here, the borders of the monument expand greatly on both sides. Through the White Cliffs, the a map of the monument will show a checkerboard of ownership including BLM, state and private with the borders of the monument extending only a few miles on either side of the river. However, through the Badlands, the amount of private land decreases dramatically, and the borders of the monument extend to 15 miles on either side. From the pictures one can tell why - the land is absolutely rugged, vast and impassable in parts. Here, reverence gives way to sheer respect for our wild places.

The first picture below shows the Judith Landing Bridge in the distance. Notice how the landscape changes. In the lower left hand corner of the picture is Holmes Rapids/Holmes Council Island, river mile 91.8. The group of rapids and island are named after the head boatman of the Stevens 1855 Council Expedition. These features proved to be regularly noted obstacles for steamboats. Just after this area, the Wild Designation begins, which means, other than the ferry (pictured in the second picture) the river corridor is largely inaccessible by land with essentially primitive shorelines.

The second picture shows a long, rugged gravel road (#1) leading to the third car ferry on the river, McClelland/Stafford Ferry (#2), river mile 101.8, and (#3) the road leading up and out to the other side of the valley. Jack and Rena McClelland started the ferry in 1921. Today, it’s a free service, but don’t be fooled, the road in and out is not to be underestimated especially if at all wet from rain or runoff moisture.

The third picture shows, along with the expansiveness of the Badlands, a dispersed campsite known as Greasewood Bottom, river mile 109.6. Do you see the two trees on the left side of the bank towards the middle and right hand side of the photo? Yes, how small these massive cottonwoods look from above! In recent years, one of these trees has been inhabited by a nesting pair of Bald Eagles. Federal law states you are not allowed to camp overnight within a quarter of a mile of a nesting pair of eagles. We like to quickly stop here for lunch, and we often see Bighorn Sheep in this area.

Ah, my favorite campsite on the entire river, Gist Bottom or Bullwacker Creek, river mile 122.6. The grove of trees in the first picture towards the bottom middle designates the campsite. The feature directly across from the grove of trees is immense and mesmerizing, and we often see Bighorn sheep drinking water then spending the evening climbing back up to the safety of the cliff. From the second picture you can see Bullwacker Creek meandering down the drainage and spilling into the mighty river. This site was recently ravaged by a significant ice jam and flooding, but it remains a majestic site with many opportunities to explore, hike and relax. First, there are two homesteads, Ervin Dugout and Gist Ranch. John Ervin’s cabin just on the other side of Bullwacker Creek is small but well-maintained. His story is contained in the guidebook and is one of the most interesting. Just behind the camp is the Gist Ranch, which was still in use by the family until 1980 when it was sold to the BLM.

If you continue past the primitive, disappearing road behind the homestead, you can hike back into the drainage and up to the top. It is about 3 miles with several steep portions. You will first come upon a large and unique geologic feature, called a diatreme (circled in picture two). From the geology section of the guidebook: “Diatremes are an unusual and uncommon type of igneous intrusion, but are important because in some places in the world they are associated with diamond deposits…. They consist of a matrix of hardened magma, which included fragments of deeper rocks through which the magma passed as it rose from unusually great depths. This texture indicates that they were emplaced with great explosive force, perhaps due to the presence in the magma of high pressurized carbon dioxide gas that helped the magma to blast its way upward, fracturing the rock that was in its path, and then transporting these broken fragments upward to be incorporated within the solidifying magma.”

If you continue back and up into the drainage, end up on top, follow the road, you can eventually make a look back to camp. This hike is known as the Snake Point Hike, for a total of 10 miles, and takes you to Clark’s viewpoint. The fourth picture shows how vast the prairie landscape is above with the river and campsite barely discernable. Here, the intrepid explorer thought he first spotted the Rocky Mountains (actually the Little Belt Mountains, an outlier of the Rockies.) He stated, “From this point I beheld the Rocky Mountains for the first time with certainty…(they) were covered with snow and the sun shown on it in such a manner as to give me a most plain and satisfactory view, whilst I viewed those mountains I felt a secret pleasure in finding myself so near the head of the heretofore conceived boundless Missouri; but when I reflected on the difficulties which this snowy barrier would most probably throw in my way to the Pacific Ocean, and the sufferings and hardships of my self and party in them, it in some measure counter balanced the joy I had felt in the first moments in which I gazed on them.”

All in all, this camp and surrounding area hold a very near and dear place in most guides’ hearts. We often opt to spend a layover day here. We call layover days ‘river gold’ because you don’t have to pack up camp or load canoes but rather hike, explore, relax and unpack!

Past Gist Bottom, we fly over Cow Creek, Kipp Homestead, the Nez Perce Nee-Mee-Poo Trail and Cow Island, river mile 124.5 - 126.5.

The Cow Creek Drainage is mostly privately owned but does contain the Cow Creek Wilderness Study Area and several historic trails. It was also one of the only places in this area that oxen or horse teams could carry supplies by land to Fort Benton if the steamboats could go no further during low water. James Kipp claimed his homestead in 1913. He was the grandson of James Kipp, a Metis trader who helped establish Fort Union at the mouth of the Yellowstone in 1828 and who founded Fort Piegan at the mouth of the Marias River in 1831.

In June 1877, the Nez Perce led by Chiefs Joseph, Looking Glass, Tulhuulhulsuit and Whitebird left their homelands and set out for Canada to avoid being confined on a reservation and to continue to live by their customs and traditions of their ancestors. The trail begins in Oregon and follows the 1,200+ mile journey through Idaho, Wyoming and finally terminates in Montana, 40 miles from the Canadian border. The trail crosses the Missouri River here just before Cow Island (pictured).

Just beyond Cow Island we reach another astounding feature of this massive ‘moving lake,’ Horseshoe Bend and Woodhawk Bottom. From the different vantage points below, you can see the river does a full horseshoe-shaped bend from river mile 130 to 133. We usually stop here, at Woodhawk Bottom in the middle of the bend, a BLM maintained recreation and camp site, to stretch our legs, and hike up the road to a vantage point. The view from this point is a favorite and wholly unique. The bend forms a marvelous bottom land area with healthy cottonwood tree groves and a terrific swimming hole in moderate to low water. It is possible to drive into this recreational area, but, again, the road is not for the faint at heart and is usually nearly impassable.

Just a few more minutes and we passed over the Charles M. Russel National Wildlife Refuge, starting at river mile 138.9, encompassing 1,100,000 acres and extending more that 125 air miles east of this point. We caught sight of the James Kipp Recreational Area, river mile 149, and Fred Robinson Bridge which designates the end of the monument. The slack water of the Fort Peck Reservoir begins about 10 miles past this point. Once you come around the corner and spot that bridge on day 6 or 7 of your canoe trip, you are flooded with emotions ranging from apprehension at the idea of reentering the bustle of society to desperately wanting a hot shower and a cheeseburger.

We decided to not push our luck anymore (remember that impending storm), and turned, b-lining it back to Helena. (Let me tell you, tiny, cute, bunny-like puffs of clouds from the ground are immense, raucous demons when you pass them in a small airplane!)

Glenn allowed Brett to fly most of the way home and even begin our decent, but I was glad when the former (the actual pilot) took the helm to land us safely back on the ground. It was an awe-inspiring adventure that will forever alter and intensify my appreciate and reverence for this treasure. And, next time, I will make sure my camera has a memory card :-)